■ America and the world waited breathlessly for the conversation of the astronauts to be radioed back to earth. For centuries, mankind had wondered what the surface of the moon would look like. Now, at last, the answers had come.

From the moment the astronauts left their space-ship, a new world unfolded before them, a world only imagined until then.

Let us recreate the memorable words of those first, courageous Americans who stood where no man had ever stood before. Let us view through their eyes the sights which no man had ever seen. These men have created a moment unique in history, and they have done it in our lifetime. May the opening up of a new world unite the countries of the earth in peace and hope for a better tomorrow.

Aldrin: Up, now you're clear . . . now move it toward me. Straight down, relax a little bit. Plenty of room. Have you lined up nicely. Toward me a little bit. Down. Okay, now you're clear ... You're touching the . . . hinge ...

Armstrong: What hinge?

Aldrin: . . . roll to the left. Okay, now you're clear. You're lined up on the platform. Move your left foot to the right a little bit. Okay, that's good.

Armstrong: Okay, now I'm gonna check ... here.

Aldrin: Okay, you're not quite squared away. Go to the, go right a little. Now you're even . . . That's good. Got plenty of room to your left.

Armstrong: How am I doing?

Aldrin: You're doing fine.

Aldrin: All right now you want this bag?

Armstrong: Yeah. Got it. Okay, Houston, I'm on the porch.

Houston: Columbia, Columbia, this is Houston. One minute, 30 seconds to LOS, all systems, go, over.

Armstrong: Need a little slack?

Armstrong: I need more slack, Buzz?

Aldrin: No, hold it just a minute.

Armstrong: Okay.

Aldrin: Okay, everything's nice and straight in here.

Armstrong: Okay, can you pull the door open a little more? ... I'm gonna pull it now .. . Houston, the MESA came down, all right.

Houston: This is Houston, Roger, we copy and we're standing by for your TV.

Armstrong: Houston, this is Neil. Radio check?

Houston: Neil, this is Houston, loud and clear. Break, break. Buzz this is Houston, radio check and verify TV circuit breaker's in.

Aldrin: Roger, TV circuit breaker's in ... Loud and clear.

Houston: Roger. And, we're getting a picture on the TV.

Armstrong: You had a good picture, huh?

Houston: There's a great deal of contrast in it and currently it's upside down on our monitor, but we can make out a fair amount of detail.

Aldrin: Okay, would you verify the position, uh, the opening I had to have on the camera?

Houston: Stand by. Okay, Neil, we can see you coming down the ladder now.

Armstrong: Okay, I just checked getting back up to that first step .. . ladder didn't collapse too far, but it's adequate to get back up. It's a pretty good little jump.

Houston: Buzz, this is Houston, F-2, one one-sixtieth second for shadow photography on the sequence camera.

Aldrin: Okay.

Armstrong: I'm at the foot of the ladder, the LM foot pads are only depressed in the surface about, uh, one or two inches, although the surface appears to be very very fine-grained as you get close to it. It's almost like a powder down there. It's very fine. I'm going to step off the LM now. That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

Armstrong: The surface is fine and powdery. I can pick it up loosely with my toe. The dirt adhered in fine layers like powdered charcoal to the, uh, to the sole and insides of my boots. I only go in, oh, an eighth of an inch, but I can see footprints of my boots and the treads and the fine, sandy particles.

Houston: Neil, this is Houston, we're copying.

Armstrong: There seems to be no difficulty in moving around, as we suspected. It's even perhaps easier than the simulations of one-sixth G (one-sixth earth gravity) that we performed in various simulations on the ground. No trouble to walk around. Okay, the descent engine did not leave a crater of any size. It's, uh, there's about one-foot clearance from the ground. We're essentially on a very level place here. I can see some evidence of rays emanating from the descent engine, but very insignificant amount. Okay, Buzz, we ready to bring down the other camera?

Aldrin: I'm all ready. I think it's been all squared away in good shape.

Armstrong: Okay.

Aldrin: Have to pay out all the LEC (lunar equipment conveyor). Looks like its coming out nice and evenly.

Armstrong: Okay, it's quite dark here in the shadow and a little hard for me to see that I have good footing. I'll work my way over into the sunlight here without looking directly into the sun.

Aldrin: Okay . . .

Aldrin: Say, I think you're pulling the wrong one . . .

Armstrong: I'm just. . . okay, I'm ready to pull it down now. There's still a little left in the . . .

Armstrong: Looking up at the LM, I'm standing directly in the shadow now, looking up at Buzz in the window, and I can see everything quite clearly. The light is sufficiently bright back-lighted into the front of the LEM, but everything is very clearly visible . . .

[interruption].. . installed on the RCU (remote control unit).

Armstrong: Still in the LEC on the secondary struts . . .

Aldrin: I'll step out and take some of my first pictures here.

Houston: Roger, Neil, we're reading you loud and clear, getting some pictures and the contingency sample.

Houston: Neil, this is Houston, did you copy about the contingency sample, over?

Armstrong: Roger, gonna get to that just as soon as we finish these pictures . . .

Aldrin: Okay, that's good. Okay, the contingency sample is down . . . It's a little difficult to dig through the crust. ..

Armstrong: It's very interesting. It's a very soft surface. But here and there where I plug with the contingency sample collector I run into very hard surface, but it appears to be very cohesive material of the same sort. Try to get a rock in here. Just a couple.

Aldrin: Ah, that looks beautiful from here, Neil.

Armstrong: It has a stark beauty all its own. It's like much of the highest desert of the United States. It's, uh, different, but it's very pretty out here. Be advised that a lot of the rock samples out here, the hard rock samples, have what appear to be vesicles—small, thin-walled cavities in the surface. Also I'm looking at one now that appears to have some sort of fenecrest.

Houston: Houston, Roger, out.

Aldrin: Okay, the handle is off the ... it's about, oh, six or eight inches into the surface . . .

Armstrong: I'm sure I could push it in further, but it's hard for me to bend down farther than that. You can really throw things a long way up here.

Armstrong: That pocket open, Buzz?

Aldrin: Yes, it is. It's not up against your suit though. Hit it back once more. More toward the inside. Okay, that's good.

Armstrong: Contingency sample is in the pocket. If uh, oxygen is 81 per cent. I'm in minimum flow.

Houston: This is Houston. Roger, Neil.

Aldrin: Okay.

Aldrin: And I've got eight zero per cent. . .

Armstrong: Are you getting a TV picture now, Houston?

Houston: Neil, yes we are getting a picture. You're not in it at the present time. We can see the bag on the LEC being moved by Buzz, though. Here you come into our field of view.

Aldrin: Okay, you read for me to come out?

Armstrong: Just stand by a second, I'll move this over the handrail. Okay?

Aldrin: Okay, that's got it. Are you ready?

Armstrong: All set. Okay, you saw what difficulties are .. . I'll try to watch your . . . from underneath here.

Aldrin: All right the backup camera is on.

Armstrong: Okay . . . looks like it's clear and okay . . . there you go, you're clear.

Aldrin: Okay, you need a little bit of arching of the back to come down . . . How far are my feet from the edge?

Armstrong: Okay, you're right at the porch.

Aldrin: Now a little, uh, foot movement . . . arching of the back.

Armstrong: Looks good.

Houston: Neil, this is Houston. Based on your camera transfer with the LEC do you foresee any difficulties in the SRC (sample return container) ? Over.

Armstrong: Negative.

Aldrin: Now I'm gonna back up and partially close the hatch. Making sure not to lock it on my way out.

Armstrong: A pretty good thought.

Aldrin: It's our home for the couple of hours and we want to take good care of it.

Aldrin: Okay, I'm on the top step and I can look down over the RCA and . . . it's a very simple matter to hop down from one step to the next.

Armstrong: I found it to be very comfortable, and walking is also very comfortable. You take three more steps and then a long one.

Aldrin: I'm going to leave that one foot up there and both hands down to about the fourth rung up.

Armstrong: There you go.

Aldrin: Okay, now I think I'll do the same.

Armstrong: Little more, about another inch. There you got it.

A

ldrin: It's a good step.

Armstrong: Yeah, about a three-footer.

Aldrin: Beautiful view.

Armstrong: Isn't that something? Magnificent sight out here.

Aldrin: Magnificent desolation.

Aldrin: Looks like the secondary strut had a little thermal effect on it right here, Neil.

Armstrong: Yeah, I noticed that.

Aldrin: Very, very fine powder, isn't it?

Armstrong: Isn't this fine?

Aldrin: Right in this area I don't think there's much of anything . . . fine powder . . . hard to tell whether it's a clod or a rock.

Aldrin: Reaching down fairly easy. Getting my suit dirty at this stage. The mass of the backpack does have some effect . . . there's a slight tendency, I can see now, to, uh, (go) backwards due to the soft, very soft texture.

Armstrong: Yeah, you're standing on a rock, big rock there now.

Aldrin: No crater there at all from the engine.

Armstrong: No.

Aldrin: Well, see that probe over on the, uh, the minus "Y" strut, broken off?

Armstrong: Yeah, it did, didn't it? Other two both bent over.

Aldrin: Can't say too much for the visibility right here without the visor up.

Houston: Say again, please, Buzz, you're cutting out.

Aldrin: I say that the rocks are rather slippery.

Houston: Roger.

Aldrin: Powdery surface when it's on there, it's filled up all the very little fine pores of his suit. . . tend to slide over it rather easily.

Armstrong: Traction seems quite good . . . least in our area.

Aldrin: About to lose my balance in one direction and recovery is quite natural and very easy. And moving our arms around doesn't... not quite that light-footed.

Armstrong: I have the insulation off the MESA (modularized equipment stowage assembly) now and the MESA seems to be in good shape.

Aldrin: Have to be careful that you're leaning in the direction you want to go. Otherwise you. . . in other words you have to cross your foot over to stay underneath where your center of mass is.

Aldrin: And, Neil, didn't I say we might see some purple rocks?

Armstrong: Find a purple rock?

Aldrin: Nope. Very small, sparkly fragments are ... in places . . . First guess is some sort of diotite, a brown mica substance. You don't dig down more than a quarter of an inch (apparently referring to footprints).

Armstrong: Okay, Houston, I'm gonna change lenses on you.

Houston: Roger, Neil.

Armstrong: Okay, Houston, tell me if you've got a new picture.

Houston: Neil, this is Houston. That's affirmative. We're getting a new picture. You can tell ifs a longer focal-length lens. And for your information, all LM systems are go, over.

Armstrong: We appreciate that, thank you.

Aldrin: Neil is now unveiling the plaque . . .

Armstrong: We haven't read the plaque, we'll read the plaque that's on the front landing gear of this LM. This is two hemispheres, one showing each of the two hemispheres of earth. Underneath it says: "Here men from the planet earth first set foot upon the moon, July, 1969, A.D. They came in peace for all mankind." It has the crew members' signatures and the signature of the President of the United States.

Armstrong: Ready for the camera? I'll get it...

Aldrin: Houston, how close are you able to get things in focus?

Houston: This is Houston. We can see Buzz's right hand. It's somewhat out of focus. I'd say we were focusing down to probably, oh, about eight inches to a foot to behind the position of his hand where he's pulling out the cable.

Armstrong: Something interesting in the bottom of this little crater here.

Aldrin: Getting a little harder to pull out here.

Public Information Officer: You stand on the ladder facing forward, the minus "Y" strut is the landing gear to your left.

Armstrong: . . . How far am I, Buzz?

Aldrin: Forty, fifty feet. Why don't you turn around and let, uh, let them get a view from there and see what the field of view looks like?

Armstrong: I don't want to go into the sun if I can avoid it.

Aldrin: Houston, how's that field of view gonna be, to pick up the MESA?

Houston: Neil, this is Houston. The field of view is okay. We'd like you to aim it a little bit too much to the right. Can you bring it back left about four or five degrees? Okay, that looks good.

Armstrong: I haven't stopped to even set it down yet. That's the first picture in the panorama. It's taking about north, northeast. Tell me if you've got a picture, Houston.

Armstrong: Okay, now this one's right down sun, straight west, and I want to know if you can see an angular rock in the foreground.

Houston: Roger we have a large, angular rock in the foreground and looks like a much smaller rock a couple of inches to the left of it, over.

Armstrong: All right, and on beyond it about ten feet is an even larger rock that's very rounded. That rock is about, uh, the closest one to you is sticking out of the sand about one foot.

Houston: Roger.

Aldrin: Neil, I've got the table out, the bag deployed.

Houston: We've got this view, Neil . . . and we see the shadow of the LM.

Armstrong: Roger, the little hill just beyond the shadow of the LM is a pair of elongated craters, about, uh, well, the pair together is forty feet long and twenty feet across and they're probably six feet deep. We'll probably get some more work in there later.

Houston: For a final orientation, we'd like it to come left about five degrees, over. Uh, back to the right about half as much.

Armstrong: Okay?

Houston: Okay, that looks good, there, Neil.

Aldrin: Okay, you can make a mark, Houston, at . . . and, incidentally, you can use the shadow that the . .. one of these small depressions .. . two to three inches ... I can see exactly what the Surveyor pictures showed when they pushed away a little bit . . . through the upper surface of the soil and about five or six inches ... breaks loose ... caked on the surface when in fact it really isn't.

Armstrong: I noticed in the . . . where we had footprints nearly an inch deep but the soil is very cohesive and it will retain a slope of probably seventy degrees . . .

Houston: Columbia, Columbia, this is Houston. AOS acquisition of signal, over.

Collins: Houston, Columbia on the high gain, over.

Houston: Columbia, this is Houston reading you loud and clear.

CoUins: Yeah, read you loud and clear. How's it going?

Houston: Roger, the EVA is progressing beautifully. I believe they're setting up the flag now.

Collins'. Great.

Houston: I guess you're about the only person around that doesn't have TV coverage of the scene.

Collins: Roger, and I, don't mind a bit. How's the quality of the TV?

Houston: Oh, it's beautiful, Mike. Really is.

Collins: Oh, gee, that's great. Is the lighting halfway decent?

Houston: Yes, indeed. They've got the flag up now, and you can see the stars and stripes on the lunar surface.

CoUins: Beautiful. Just beautiful.

Aldrin: I'd first like to evaluate the various paces that a person can ... traveling on the lunar surface. I believe I'm off your field of view, is that right, Houston?

Houston: That's affirmative, Buzz. You're in our field of view now.

Aldrin: All right. You do have to be rather careful, uh, to keep track of where your center of mass is. Sometimes it takes about two or three paces to make sure that, uh, you've got your feet underneath you. About two or three or maybe four easy paces can bring you to a fairly smooth, uh, stop. Switch directions, it's like a football parry, you just have to put out to the side and tread a little bit.

Aldrin: So-called kangaroo hop. Does work but it seems that your forward ability is not quite as good as it is in the conventional one foot after another...

Houston: Tranquility base, this is Houston. Can we get both of you on the camera for a minute, please?

Armstrong: Say again, Houston.

Houston: Roger, we'd like to get both of you in the field of view of our camera for a minute. Neil, and Buzz, the President of the United States is in his office now and would like to say a few words to you, over.

[President Nixon then spoke to the astronauts.]

Aldrin: Uh, Houston, it's very interesting to note that when I, uh, kick my foot... no atmosphere here and this gravity . . . they seem to leave and most of them have about the same angle of departure and velocity. Where I stand . . . large portion of them will impact at a certain distance out . . . highly dependable on ... initial trajectory upward.

Houston: Roger, Buzz, and Columbia, this is Houston, when you track out of high-gain antenna limits request omni delta, omni delta, over.

Aldrin: I've noticed several times in going from the sunlight into shadows that just as they go in, there's an additional reflection off the LM, that, along with the reflection of my face onto the visor, makes visibility very poor, it's just in the transition, sunlight into the shadow.

Aldrin: I eventually have so much glare coming onto my visor . . . then it takes a short while for my eyes to adapt... lighting conditions. Visibility, as we said before, is not too great but with both visors up . . . sort of footprints we have and the condition of the soil. Then after being out in the sunlight for a while it takes—watch it, Neil, Neil you're on the cable.

Armstrong: Okay.

Aldrin: Yeah, pick up your right foot. Right foot. It's still, your toe is still hooked in it.

Armstrong: That one?

Aldrin: Yeah, it's still hooked in it. Wait a minute. Okay, you're clear now.

Armstrong: Thank you.

Aldrin: Now let's move that over this way.

Aldrin: The, uh, blue color of my boots has completely diseappeared now into this, oh, we don't know exactly what color to describe this other than grayish-cocoa color. Appears to be covering most of the whiter particles.

Houston: Buzz, this is Houston, you're cutting out on the end of your transmissions. Can you speak a little more closely into your microphone, over.

Aldrin: Roger, I'll try that.

Houston: Beautiful!

Aldrin: Well, I had that one inside my mouth that time.

Houston: Sounded a little wet.

Aldrin: In general, time spent in the shadow doesn't seem to have any thermal effects ... inside our suit. There is a difference of course in the . . . radiation in the helmet . . . so . . . feel little cooler in the shadow than in the sun.

Houston: Columbia, this is Houston, over.

Collins: Houston, Columbia, on delta. ■

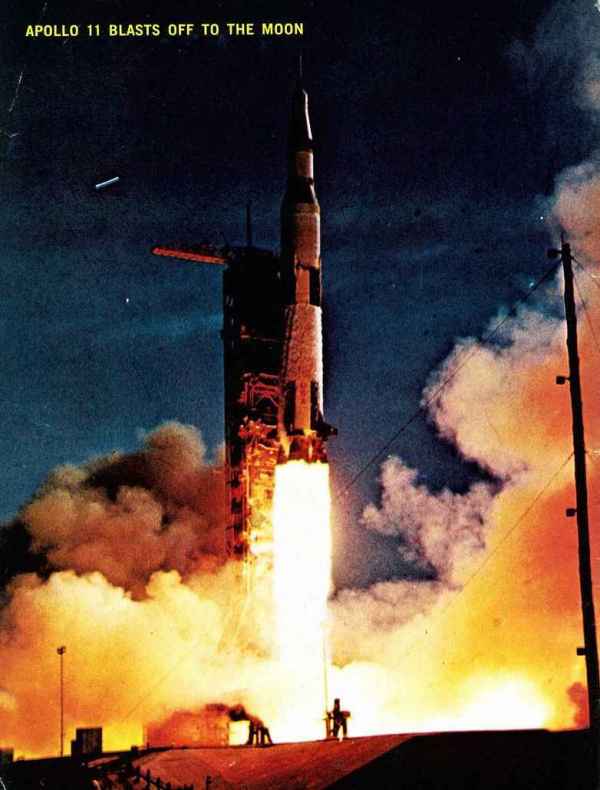

On the morning of July 16, 1969, hundreds of thousands of spectators converged on Cape Kennedy to witness the beginnings of man's greatest adventure in space exploration. The earthlings turned the roads leading to the Cape into something of a New York City traffic jam—but all was calm by early morning hours as millions of people turned their eyes toward the Apollo launch-pad at the scene of the liftoff and via television transmission across the world. Astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins and all of us who watched, counted down the final seconds to blast off.

What was it like for the moon crew—sitting in the Apollo 11? According to Colonel James A. McDivitt, the commander of the Apollo 9 flight which orbited the earth in March, the astronauts didn't have much of a view while they were waiting on the pad. Three of their five windows were covered by protective shields. One window looked into the White Room, the small chamber connecting the spacecraft with the launching gantry. The other window, their fifth opening, looked straight up into the sky. McDivitt tells us that sitting in the rocket where the astronauts were strapped in, we would have the feeling or sensation of sitting in a tree- top in a light wind.

At ignition, the astronauts did not see the fire, the smoke from the Saturn. They felt a steadily increasing vibration as the five engines in the first-stage booster built up to ninety percent of their thrust. It takes seven and a half million pounds of thrust to lift the rocket off the launch pad. With all that force pushing them up into the heavens, the three astros felt only a slight force against them in their seats. The noise for the spectators was almost ear splitting, but, with the headsets on, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins heard little of the rocket blast sounds that shattered the Cape area. Perhaps it can best be described as a similar sensation to that of sound sensation experienced by any of us during takeoff of a commercial jetliner.

During the moments of liftoff, Armstrong held tight to the "Abort" handle—in the event that anything went wrong. If liftoff was unsuccessful, the abort mechanism would have ejected the astronauts immediately. But the liftoff was A OK—a perfect blast off.

The Apollo 11 picked up speed as it ascended into the sky. Soon, one of the five rocket engines in the booster shut off. After a little more than two minutes after blast off, spectators could see the first-stage booster dropping off. Then the S-II ignited and burned for about seven minutes. Then the escape tower was blown off and all windows were revealed—giving the astros their first good view of the heavens and earth. The third stage of rocket ignitions thrust the Apollo into earth orbit.

July 16th—the moment: 9:32 a.m. Destination—the moon. It was the beginning of a nine-day exploration that will now go down in history. The moonshot and the lunar landing and moonwalk were witnessed by an approximated audience of over 600 million people of the world. On that morning in Cape Kennedy, some 3,500 journalists (from over 55 countries) had gathered to record the liftoff and the events leading to man's landing on an alien world.

For everyone, it was an exciting experience. For those who had come to the Cape to eye-witness history, it was an experience never to be forgotten. Almost all of the spectators interviewed, told of their great pride and confidence in the moonshot. And when asked if they would someday like to travel to the moon, they answered with enthusiastic anticipation. Yes, the average American looks forward to the day when space travel will be an everyday occurrence.

Three earthlings, the wives of the astronauts, watched the lift off with tears in their eyes and prayers in their hearts. The three wives were not together—they witnessed the blast off from different areas. Here are their statements at that historical moment:

Pat Collins (who watched on her TV set at home): "It's sitting there forever. Maybe we should push ... there it goes. It's beautiful."

Joan Aldrin (watching with dignitaries gathered at the Cape): "This is the part I like best." Then as the Saturn engines ignited, she began to cry and covered her eyes with a handkerchief.

Jan Armstrong (who watched the lift off from a boat at the Cape, three miles from the launch pad): "We're going to go. We're going to go." Her arms were around her sons, Mark and Ricky.

Back in Wapakoneta, Ohio, Neil Armstrong's parents viewed the lift off in the living room. Their son was to be the first man on the moon. Their prayers were with Neil during lift off and throughout the moon mission. As the rising, flaming Apollo lifted upward into the sky, tears ran down his mother's cheeks as she said, "There he goes." The skipper and his crew were on their way—destination moon!

President Nixon's conversation with astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they stood on the surface of the moon:

President Nixon: Neil and Buzz, I am talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House. This certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made from the White House.

I just can't tell you how proud we all are of what you have done for every American. This has to be the proudest day of our lives. For people all over the world I am sure they too join with the Americans in recognizing what an immense feat this is. Because of what you have done the heavens have become a part of man's world.

As you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to earth.

For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this earth are truly one. One in their pride in what you have done, one in our prayers that you will return safely to earth.

Neil Armstrong answered: Thank you, Mr. President. It is a great honor and privilege for us to be here representing not only the United States but men of peaceable nations with an interest and a curiosity and a vision for the future. It is an honor for us to be able to participate here today.

The President answered: I thank you very much. All of us look forward to seeing you on the recovery ship Hornet on Thursday.

Armstrong answered: Thank you.■

Neil A. Armstrong, the first man in history to set foot onto another world, is a complex personality. At the age of 38, Armstrong still retains a boyish smile, and his quiet reserve, which is often mistaken for coldness, is, in fact, one of the many signs which tell that he is shy. Those who are close to him say that he is an extremely warm individual, although he can also be tightly controlled and capable of a highly rational intensity. He seldom lets on that he is nervous or disturbed about anything. Observers report that his feelings are expressed only in the form of small gestures. He may blush, pull on an earlobe, or rub his nose. Sometimes, he stammers. "Actually," says Dr. Charles A. Berry, chief of NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center, "he's bashful."

Armstrong has done almost everything any man could hope to do in the field of endeavor he loves best: flying. On a number of occasions, he has been perilously close to death, but his calm, steady approach to things has always carried him through the most frightening experiences. On one occasion, when he was flying combat missions in Korea, he was shot down by Chinese anti-aircraft guns and was forced to parachute behind his own lines. On another flight, his wingtip was broken off by a cable that the Communists had stretched across a valley. In spite of such difficulties, Armstrong completed 78 combat missions.

No one could have been better suited to being an astronaut than Neil Armstrong. His mother recalls that his bedroom had always been crammed with model airplanes, books about flying, and aircraft drawings from his earliest years. To buy these models, young Armstrong earned money at after-school jobs, cutting grass and working as a stock boy in an Ohio drugstore.

He was born in his grandparents' house on a farm six miles southwest of Wapakoneta, Ohio, which could easily be called a model of the American small town. Its broad, tree-lined streets and an abundance of old-fashioned two-story clapboard houses, give Wapakoneta an air of gracious, gentle intimacy. Armstrong's father, Stephen, and his slim, attractive mother, Viola, created the atmosphere which made it possible for Neil to develop into the high-school student under whose yearbook photograph was written: "He thinks, he acts, 'tis done." Neil says that his parents were characteristic of the area where he grew up. "The people of that community," he said, "felt it was important to do a useful job and to do it well." His mother spent many long hours reading to her young son and conversing with him about almost everything under the sun.

His interest in flight began when his family took him on a casual excursion to the Cleveland airport at the age of two. As a teen-ager, he worked as a grease monkey at Wapakoneta's small airport, and before he had received a driver's license, he'd earned a pilot's license at the age of sixteen.

Paul Haney, the former Voice of Apollo, says that flying is like a religion to Neil Armstrong. When he talks about the Wright Brothers his voice is almost hushed. "He took along a part of the Wright flyer on his Gemini mission," recalls Haney, "like it was a piece of the True Cross."

An amateur astronomer, Jacob Zint, of Wapakoneta, erected a back-yard observatory where Neil Armstrong was a frequent visitor. Mr. Zint recalls that most of the kids in town would look for only two or three minutes each through his telescope, but that "Neil would look and look and look." The telescope brought the moon to within 1,000 miles for viewers.

Neil's brother, Dean, recalls that Neil was always smaller and younger-looking than most of his classmates. He was not particularly athletic, and seldom had dates while he was in high school. Even at Purdue University, he remained shy and unassertive. Not until he returned from Navy combat did he seem to have developed an underlying confidence in himself.

He was bigger, stronger, and more experienced when he returned to college after serving in the Navy. He got his degree in aeronautical engineering at Purdue and then joined the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. For the next seven years, Armstrong trained at Edwards Air Force Base, becoming one of the most accomplished test pilots in the world. Instead of living in the nearby town of Lancaster, California, with most of the other test pilots, Neil and his wife Janet chose to restore a forest ranger's cabin in the isolated foothills of the San Gabriel mountains. During this period, the Armstrong family was struck by tragedy: the death of their only daughter, Karen, of a brain tumor. His surviving children are Eric, 12, and Mark, 6.

Janet, whom he married in 1956, was a campus sorority queen from Evanston, Illinois. A typical family outing with the Armstrongs finds Neil, Janet, and the boys scuba diving at some weekend retreat.

In 1962, Armstrong applied for astronaut training and was accepted into a class which included Frank Borman, James A. McDivitt, the late Edward H. White, and five others. He became the commander for the Gemini 8 mission, and his co-pilot, David R. Scott, assisted him in man's first attempt to link two craft together in space. When the craft were linked, however, they began to spin widely. Armstrong was able to bring them under control, and made an emergency landing in the Pacific.

Last year, Armstrong once again showed his piloting skill when a jet-powered training craft, in which he was carrying out tests, suddenly skittered out of control. Aware of the fact that the craft was about to flip upside down, Armstrong pushed the ejector button and parachuted to safety. The jet crashed and burned. Asked how he felt about such a narrow escape, Neil replied that it had been "no worse than some of the scares I received when driving an automobile." He admits, however, that his close scrapes with death have prevented him from getting too confident.

Neil Armstrong's quiet modesty extends to his own spectacular mission on the moon. Speaking in soft, unassertive tones, he says, "If historians are fair, they won't see this flight like Lindbergh's. They'll recognize that the landing is only one small part of a large program."

•Even when he was only three years old, Buzz Aldrin was interested in voyages. Here, in a 1933 photo, the astronaut-to-be smiles at the camera. Little did he know that he would be one of the first men on the moon, only thirty-six years later. Buzz grew up surrounded by a houseful of women. While his father fought in World War 11, the youngster was left at home to be "man of the house"

■ Colonel Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Jr., was nicknamed "Buzz" because his sister, Fay, couldn't pronounce "brother." She said "Buzzer," and it was shortened to "Buzz" when the astronaut was only ten years old.

Buzz Aldrin is no stranger to the word "moon." It was his mother's maiden name. Buzz's father, a retired Air Force colonel, now 73, went off to war at Guadalcanal in 1943, and left his only son in a household full of women. "You're the man of the house now," he said, before leaving. Buzz grew up in the rich, serene environment of a New York suburb, Montclair, New Jersey. He had a nursemaid, two sisters, his mother, grandmother (Mrs. Moon) and a cook to look after him. But when his father returned from serving in World War II, he recalls that Buzz had "completely grown up."

What sort of youngster was Buzz Aldrin? His sister, Fay, remembers him as a "typical rascal boy, a pest.' His childhood nursemaid remembers him as "very active" although quite easy to manage. He did have a tendency to run off and disappear, however, causing the household a great deal of worry and anxiety.

He was always a first-rate athlete. As a youngster, he set up hurdles in the back yard of the three-story Aldrin home, and he liked to walk on stilts, chin, and do calisthenics. Buzz's mother demanded excellence of her children, but always did so in a "nice way." Although she wanted them to be sure to do their best in every situation, she never attacked their self-respect or ridiculed them. Buzz grew into a happy, healthy blond teenager who was always glad to do whatever he could to please his mother.

Buzz entered the first grade a year earlier than most of his schoolmates because he was bored with the second year of kindergarten (which was then required in Montclair). His second-grade teacher, Miss Rita Hogan, now retired, says that he strained every nerve "to prove he could make good." In school, "he was all business," said Miss Hogan.

Buzz's father, who has watched his son's career with intense interest, is a proud man who also set flying records in 1929, the year before his son was born. He learned physics at Clark University under Dr. Robert Goddard, the father of modern American rocketry, taught himself to fly airplanes, and started what is now the Air Force Institute of Technology at Dayton, Ohio.

In high school, Buzz's athletic prowess continued to blossom. For a while his grades suffered at the expense of his passion for sports, but eventually his parents convinced him that his college prospects would be nil if he did not apply himself AA to his studies. He graduated in the upper tenth of his class. His math teacher at Montclair High, William Filas, says that Buzz "enjoyed success where you can see success, as in solving math problems." Buzz was a natural in mathematics and had a real drive to excel. "He gave the appearance of being absolutely sure of himself at all times," said Mr. Filas.

Buzz graduated third in the class of 1951 at the United States Military Academy. He decided to become a pilot. He went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and won a doctor of science degree in astronautics in 1963. His doctoral dissertation on orbital mechanics and space rendezvous became one of the bibles of space flight. He dedicated his thesis to the astronauts with the prophetic hope, "Oh, that I were one of them!"

Today, Buzz Aldrin is the father of three children, J. Michael, 13, Janice, 12, and Andrew, 11. His wife, Joan, is a lovely, light-haired woman from Hohokus, New Jersey. The Aldrin family likes to relax on the New Jersey shore, where they sit around in the sun, eat "corn on the cob, and go swimming."

■ Air Force Lt. Col. Michael Collins, 38, dislikes the prospect of becoming a world hero. "There are two kinds of people in the world," he says, "those who like publicity and those who prefer to do without it. I prefer the latter." Still, Collins is thought to be the best-liked of the astronauts. ''If a contest were held for 'Everybody's Favorite Astronaut,'" says a close friend, "Collins would win it going away and then discreetly refuse the title."

Collins was born in a plush apartment house in Rome, Italy. His father's ancestry extends to Ireland, and his mother's to pre- revolutionary America. The elder Collins was an Army general, who was military attache in Rome when Michael was born. It was from his father, James, that Michael got his quick athletic bent.

Collins' mother, a slight, well-mannered woman who lives in Washington, D. C., first imbued Michael with his love for books and music. She always made sure that her children appreciated what was best in the world, and when the family moved from one city to another, she took Michael and his sisters to museums, theatres, churches, and other public places so that they might get a better glimpse of the treasures of civilization.

Although the Collins household was a military one, there was no military stiffness in evidence. Whenever they moved to other locales, Mrs. Collins made sure that her children were familiar with the languages spoken by the citizens in those areas.

Before his twelfth birthday, Michael had moved to six different locations: Rome, Oklahoma, Governor's Island, Baltimore, Texas, and Puerto Rico. His father commanded the Army's Puerto Rican Department, and the family lived in a giant, sprawling mansion called Casa Blanca.

The constant moving about did not seem to disturb Michael at all. "I think that a life like that is good for a kid," he said, musing on the many places he's lived. "It's interesting, and on the balance I think it's an advantage." The Collins family drew very close to one another, and its gypsy life caused each member to support and help the other.

When he was twelve, Michael was sent to St. Alban's School for Boys in Washington, D. C. The fashionable school, on secluded, leafy grounds adjacent to the Washington National Cathedral, became the center of Michael's life for the next few years. He lived an almost Spartan existence, sleeping in a small cubicle resembling a monk's cell. Here, say his teachers, he became widely known as one of the chiefs of mischief. "He had an immobile face," said one of the schoolmasters. "You always wondered what he was concocting."

At St. Albans, Michael became one of the most popular boys in school. The yearbook for 1948 noted that he was among the four most popular among his classmates. It was also noted that he was visited continually by Morpheus (the Greek god of sleep). This, of course, may have been caused by the fact that he had to get up each morning at 6:30 A.M. to serve as an altar boy in the cathedral.

In 1952, when Michael graduated from West Point, there was no evidence that he would become an outstanding American. The yearbook at West Point noted that his battle cry was "stay casual" and that "he took the cash and let the credit go and seldom heeded the distant rumble." Which is to say that he lived in the present and didn't give a thought to the morrow. It was not until he became actively involved in the space program that he really became deeply committed," said Bill Dana, a NASA test pilot who was his roommate.

Collins is happily married to a slim, dark-haired beauty, the former Patricia M. Finnegan, of Boston. They have three children.

■ They are, in most ways, three ordinary young wives and mothers. They plan meals, help the children with their lessons, visit friends and attend church on Sundays. But in one way, the three astrowives—Janet Armstrong, Patricia Collins and Joan Aldrin, are unique in history; for it was their husbands who were to be first to set foot on the moon. And while it is true that throughout history there have been men who have undertaken dangerous voyages to all parts of the earth, leaving their wives behind to wait and pray for them, yet, never before have women been left on earth while their men took off for outer space.

True, every stage of the flight of Apollo 11 had been planned as carefully and rehearsed as thoroughly as was humanly possible. However, the astrowives, like the rest of the world, must have realized that in such an enterprise as this one, there was always the possibility of an unforeseen disaster, an unexpected catastrophe that could, in an instant, rob them of the men they loved.

And yet, while fully aware of the risks that lay in store for their husbands on this first flight to the moon, the three astrowives were somehow able to present a poised, cheerful appearance to a watching world. If they had private fears or misgivings as to the outcome of the mission, they kept them locked in their hearts. What special breed of women are these three—Pat Collins, Joan Aldrin and Jan Armstrong? How do they really feel about their unique place in history?

Janet Armstrong, quiet and reserved like her husband, declined to tell reporters what her parting words to her husband were, before he took off on his historic mission. She has a strong sense of privacy, even though she knows that the eyes of the world are upon her. Behind the door of the Armstrong home in El Lago, Texas, Janet has created a private world for herself and her children, Eric, 12, and Mark, 6. "I still have to carry on the normal job of any wife," Mrs. Armstrong told reporters, shortly after the Cape Kennedy launch. She was determined to keep things running smoothly for her family here on earth.

But even after the launching had been successfully carried out, anxious hours of waiting still lay ahead for Mrs. Armstrong and the other astro-wives. There was still the landing to be made on the surface of the moon, and later, the lift-off and the start of the long journey home. There were anxious moments for Mrs. Armstrong as she waited through the crucial countdown—a failure of equipment, a miscalculation—and her husband, Neil Armstrong, could be trapped forever on the lifeless wastes of an alien world. It wasn't until the lift-off was completed that she could hug her son and breathe a sigh of relief. Her husband had started the long journey home.

How does she feel about being a part of this great adventure? In her own words, "It is an honor and privilege to share with a husband, the crew, the Manned Spacecraft Center, the American public and all of mankind this magnificent experience of the beginning of lunar exploration."

Joan Archer Aldrin, the wife of Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin, is a trim, statuesque blonde with a background in the theater. She attended Douglass College in New Brunswick, where she acted in plays and also had her own radio show on the campus station. After graduating, she acted on TV in "Playhouse 90" and "Studio One." When she first met "Buzz" Aldrin at a party, she was not tremendously impressed. "Nothing happened, no spark," she recalls. However, after he had served in Korea and returned, things changed. They were married in December of 1954. Joan, like most military wives, has had to move frequently, but this apparently doesn't trouble her. She has three children Michael ,13, Janice, 11, and Andrew, 10—they, too, seem to thrive on the life of change dictated by their father's choice of career. Perhaps their religious' training gives them the needed sense of stability so necessary to an astronaut's children.

Although Joan Aldrin is content to put her husband's career first, she still retains an interest in the theater. She is a founder and backstage worker with the Clear Creek Country Theater, and frequently performs in their plays. When her husband was about to leave on his historic mission she said good-bye with an expression right out of the world of acting: "Break a leg." This is, of course, a good-luck slogan according to theatrical superstition and is supposed to insure a successful performance. In the case of Buzz Aldrin, it certainly seems to have worked.

A friend of the family remarked: "The discipline in the Aldrin family is marvelous. Mrs. Aldrin suggests that her children think things through, and they usually come up with the decision she had in mind all along. And although she has a degree in drama, I have never seen her strike one affected pose or say one affected thing. She is a very real person."

Pat Collins, wife of Michael Collins, presides over a cheerful household, with her three children, Kathleen, 10, Ann, 7, and Michael, 6. The household also includes a German shepherd and a rabbit. The atmosphere is relaxed and happy, in spite of the inevitable stresses imposed on an astronaut's family. Pat herself describes their home life as "a few moments of tension and a lot of smiles."

One of her hobbies is gourmet cooking, a skill she acquired while her husband was stationed in Europe. A friend says of Pat Collins that she is "extremely self-reliant, and I have found that I can help her best by being unobtrusive."

These, then, are the wives of the first men on the moon. Different from one another, they have shared, in a very personal way, the greatest adventure on which mankind has ever embarked in the history of the human race.

While American astonauts stepped onto the surface of another world, the inhabitants of the planet Earth were unanimous in agreeing that their feat inspired awe, joy, and a sense of pride.

According to the European Broadcasting Union, 600 million people throughout the world viewed the moon-landing on TV screens. Uncounted millions more listened on the radio, and many others would view the great feat on films during the next few days. Many of the Communist nations, whose news media often ignored American space flights, gave favorable or impartial coverage to the awe-inspiring mission hailing the accomplishments of the U.S.

Some Americans looked to God, and others were glued to their TV sets but only a few tried to ignore the moon flight. American technology had once again proved itself to be in the vanguard, and for a few hours all of the cares, problems and difficulties of daily life were forgotten in the midst of a magnificent victory as men everywhere peered into the skies with an overwhelming sense of excitement, and a new feeling of human unity.

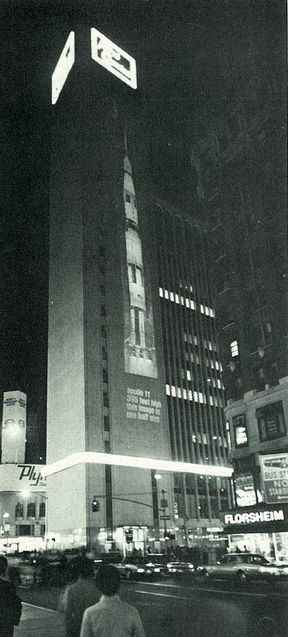

In New York's Central Park, huge TV screens representing every major network were set up to give the city's population a glimpse of the entire moon flight. A crowd of thousands braved a light rain which turned the Park into a marsh. When the first steps were taken, a roar of triumph and joy rose from the assembled masses. Firecrackers, balloons, and other wild expressions of approval were released by those who were watching. ■

It took eight years of dedicated planning and teamwork to launch the greatest adventure the world has ever known.

■ From the time Apollo ll's heroic crew stepped into their multibillion-dollar, moon-bound space capsule until the moment they splashed down safely in the Pacific, eight days later, the whole world watched and waited and held its breath. The hopes and prayers of people in every corner of the globe were focused on the three Americans whom destiny had chosen for cosmic immortality. Via televised satellite, millions of awed viewers from Baltimore to Bangkok to Buenos Aires were able to follow each step in the historic flight of the moon mission and even share some of the immeasurable thrills which the astronauts themselves experienced.

To those of us who witnessed this moment in history in the warmth and safety of our own living rooms, America's lunar journey seemed as flawless and exciting as the climax of a great science-fiction film. But this, in its own way, is merely one more supreme tribute to the manpower and determination which made this project possible. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins were the visible heroes in this great epic of human endeavor. But the scores of scientists, engineers, and technicians who pooled their time and knowledge to launch these men to the moon and back deserve the cheers and gratitude of their countrymen. For they, too, are heroes. On these pages are sketches of each major step in the moon expedition—sketches which show the talent and teamwork it took to launch and recover the mighty Apollo spacecraft.

■ The suits worn by Astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin have been described as "self-sufficient space ships." The space suit itself weighs more than the astronaut wearing it: altogether, 185 pounds, earth weight. Armstrong and Aldrin weigh about 165 pounds each, but on the moon everything weighs1 approximately one-sixth of whatsit would on earth. As you witnessed via television coverage from the moon's surface, our astros had little difficulty maneuvering in their heavy lunar suits.

The lunar space suit was worn only during the actual moon walk—different suits were worn by the astronauts to and from the moon. Suits worn for moon exploration carried their own electricity, water, oxygen, fan, refrigerator—indeed, space ships in the form of clothing. In addition, the moon suit included a sophisticated two-way radio. The radio allowed the astros to talk to each other. At the same time, it sent back signals to mission control in Houston. Nine types of information were returned to earth, including the astronauts' electrocardiograms.

The electrical power was produced by an array of silver-zinc batteries in a container about the size of a loaf of bread. The air they breathed was kept clean by lithium hydroxide and activated charcoal.

The suit's cooling unit.was cooled by the sublimation of a thin layer of ice in a honeycomb chamber through which the suit's oxygen and water passed continually.

From skin to the last outer layer of clothing, the astros were dressed like walking thermos bottles. In place of underwear, they wore a nylon covering with a network of vinyl tubes through which water circulated for cooling. Over that, a pressure garment to give the astronaut his own atmosphere. Over that, an integrated thermal micrometeor- oid garment to protect against fire, abrasion, temperature extremes, etc. Over their heads, the astros wore clear plastic pressure helmets with adjustable visors.

■ Ever since modern man's ancestors took their first shaky steps beyond the security of the cave, the human animal has been frightened and yet fascinated by the endless universe around him. When prehistoric man moved from ignorance and darkness into the sunlight of the outside world, he embarked on a great expedition into the unknown—an expedition that climaxed when the American astronauts landed on the surface of the moon.

Throughout the centuries, man has always been preoccupied with this small, round, silver globe shining in the heavens. To the ancients the moon was a symbol of love and death and immortality—all those mysterious aspects of life which pure reason could not explain. The Greeks believed that the moon was really a supernatural woman whom they called Artemis. They imagined her as a beautiful, virgin goddess who, together with her twin brother, Apollo, the Sun, ruled the universe. There were as many theories about the moon as there were ancient civilizations, and as long ago as when the first shepherd watched over his flocks at night and gazed into the vast panorama of the Milky Way, man has longed to penetrate the secrets of the moon, to give himself wings and fly beyond the trees and clouds and birds until he had reached his fantastic lunar destination. From Columbus to the Wright Brothers, from the steamboat to the first Sputnik, this has always been mankind's real aim.

Perhaps the ancient Egyptians were really the world's first explorers. Although they did not discover any new continents or chart any new sea routes, those people who dwelt along the Nile some two thousand years ago were actually primitive forerunners of today's Apollo 11 crew. Like many ancient nomadic tribes, the Egyptians were worshippers of the moon, and out of their religious convictions they were inspired to build the Great Pyramids. Reaching halfway up to the sky and only partially completed, those magnificent works of architecture still stand as a legacy of man's early determination to reach the stars. Thousands of Egyptians may have perished in the construction of those gigantic monuments, but this half-ful- filled dream of generations of Pharaohs has survived intact.

Although it wasn't until the invention of the airplane, in our own century, that people really began to take the notion of space travel seriously, writers and poets have tinkered with the idea for ages. Nearly a hundred years ago, science-fiction author Jules Verne prophecied a successful lunar expedition by man in his novel, From the Earth to the Moon. At the time skeptics ridiculed the scientific content of the book, but today it is curious to look back and note just how close Verne's literary predictions came to the actual events of the Apollo 11 mission. In Verne's fictional scheme, three adventurous Americans, led by the amazing J. P. Barbicane, decided to construct their own home-made spacecraft and head for the cosmic regions. Since the theory of jet propulsion was unknown in the nineteenth century, Verne had only his own imagination to rely on in devising a way to launch his fictional spaceship. The method he conceived of seems highly original, if slightly humorous, in retrospect. Verne simply used a cannon to shoot Barbicane and his companions out of the pull of the earth's gravity. But aside from the fact that he accurately foresaw that the first men on the moon.would someday be Americans, Jules Verne was also far more of a scientist than his contemporaries gave him credit for. His conception of a lunar vehicle—computer-controlled and manned by astronauts in oxygen-insulated spacesuits—is almost an exact replica of the actual craft which moon-lifted Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins.

Over the years there have been many elaborate hoaxes connected with the moon. In the late 1800's, Richard Adams Locke, the editor of the New York Sun, published a totally fictitious report of life on the moon as a circulation stunt. In a series of "exclusive" interviews with British astronomer Sir John Herschel, the Sun reported that Herschel had eyewitnessed whole communities of lunar "batmen" through an extraordinary new telescope. At the time of the release of the story, the eminent astronomer was actually vacationing in South Africa and was as flabbergasted as the rest of the public to read about his moon-shaking scientific discoveries.

While scientists and authors debated over the centuries as to the existence or nonexistence of lunar life, explorers were busy enlarging man's circle of the known world. With each new heroic giant step in navigation, mankind was slowly but steadily moving closer to his distant cosmic target. Folklore and mythology are filled with timeless stories of man's journeys to the stars, to the ends of the earth, to heaven and to hell. According to Greek legend, Orpheus was the first mortal to penetrate the depths of the nether world in his tragic search to recover his wife, Eurydice, from the dead. Daedalus and his son Icarus, on the other hand, fastened wax wings to their shoulders and attempted to fly to the sun. But, of course, when they came too close to their solar goal, their wings melted and they fell into the sea.

History records that the world's first great navigator was Jason of Sparta, who sailed the length of the Mediterranean with his trusty band of Argonauts in search of the precious Golden Fleece. Ulysses' ten-year Odyssey homeward, at the close of the Trojan War, the exodus of the twelve tribes of Israel from Egypt to the Promised Land, and the famed medieval Crusades are all memorable epic journeys in the history of civilization.

Heroes like Marco Polo, who navigated the first commercial trade route to the Orient, and Christopher Columbus, who stumbled upon a whole new world in the West, stand out as figures of immortal courage, imagination, and daring. And when man seemed to have reached the limits of his thirst for adventure on solid land, new giants like Sir Edmund Hillary and Admiral Robert Peary rose to take their place. Within this very century, the North and South Poles have been colonized, Mount Everest conquered, and the perimeter of the earth orbited in a one-engine, one-man airplane. Finally, when man had pitted his nerve and intellect against every conceivable challenge that this planet could offer, it was only inevitable that he should turn his wandering gaze to the still vaster Everests of the universe.

When Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin descended from their lunar capsule to plant man's first footsteps on the treacherous surface of the moon, it was their destiny to fulfill the world's most precious and most ageless dream. Now it remains the destiny of us all to transform that dream into a still greater one—the dream of universal peace. •

■ What is the moon? How did it originate? Is it a living, ever-changing body of matter, or is it inert and lifeless, a barren world completely foreign to everything within our understanding? These are some of the major questions for which the Apollo 11 flight may soon provide some answers.

Scientists at the moment hold three basic theories as to the moon's origin. Some feel that the moon was at one time a part of the earth, but somehow broke away, becoming a natural satellite. This theory was first developed by Sir George Darwin, son of Charles Darwin, more than a century ago. Other scientists of today argue that if the rotational energy and mass in both bodies were concentrated into one, the speed of rotation would still not be high enough for such a separation to occur. Furthermore, it is doubted that the moon's orbit of today could possibly be the same if such a fission had once happened.

Many scientists prefer to believe that the moon formed quite independently of the earth but was captured by the earth's gravitational pull. They believe that perhaps the moon was at one time a comet head or an asteroid slowed down enough by such gravitational forces as the sun and the earth that tidal friction was powerful enough to cause it to go into orbit around our planet. Some scientists have also suggested that there was not only one moon captured by the earth in this way, but several smaller ones, as well. These smaller moons eventually collided with the moon as we know it today, creating impact basins on the moon's surface in the process. Calculations have indicated, however, that at least 98 percent of the moon as it exists today is the original body.

However, we do know that there is a great difference in the density of the earth and the moon.

If it were true that they were formed at the same time in a similar position in the solar system, would it not seem logical that both bodies would have been formed by similar materials of about the same density?

But perhaps the moon is closer akin to the earth than many people have suspected. Many scientists feel that the moon is younger and changing much faster than was originally believed. There also seems to be evidence of the effect of volcanic activity in the past as well as the present. The experts have reported red glows coming from the craters of the moon for over ten years now. Furthermore, scientists have recently had a close look at winding canyons, referred to as "sinuous rills." These canyons look as though at one time they carried some kind of running fluid. While some believe that this fluid was water, others feel that they are collapsed lava tubes through which lava once flowed beneath the surface.

Although, to us on earth, the finding of large deposits of diamonds or gold on the moon may seem important, for the time being, it is not. For, as of now, there is no way of mining and transporting large quantities of valuable mineral products. The cheapest substance we have on earth is the most priceless substance the astronauts could find on the moon, that of water. If there is water, in the next few years, bases could be set up on the moon for extensive research over a long period of time. Some scientists believe that there exists a layer of permafrost, similar to the layers of ice found in the Arctic, insulated from the sun several feet under the moon's surface. Some of those who believe that the moon was once a part of the earth also believe that it took a large amount of water with it when it was spun away. It also is conceivable that, if the moon was a separate body to begin with and was captured by the earth's gravitational pull, its gravity may have siphoned water away from the earth's oceans. Even though, in our own time, the moon's gravity is weak, it is still powerful enough to cause our tides by pullingthe earth's seas and oceans.

Another group of scientists believe that deep within the moon there exists boiling water, the steam of which escapes through lunar fissures in a fashion similar to some of earth's geysers. Others believe that water could possibly be extracted from the moon's rocks. Since scientists have detected evidence of sulphur on the moon's surface, such an idea is not unreasonable, since sulphur is associated on earth with water-bearing or porous rocks.

At any rate, in order for man to survive on the moon for any length of time, it is necessary for him to have water for drinking, cooling electrical equipment, heating and air conditioning, and growing food.

According to Dr. George C. Mueller, chief of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's manned-spaceflight programs, a single landing on the moon will tell us no more about it than Columbus could tell us about the resources of America from a single visit to the West Indies.

But if man is to research the moon thoroughly to find the answers that have been plaguing him for centuries, he must have water to provide for a longer sojourn.

Perhaps from lunar exploration, we will learn some of the answers to the questions of the life and death of the stars and of our own planet. Maybe biologists will be able to learn the meaning of life and the infant's first question to his mother, "Where did I come from?" and the adult's question, "Why am I here?"

■ When the Apollo 11 astronauts splashed down safely in the Pacific on July 24, 1969, the world's greatest journey had come to an end. Back home on earth once more, the three illustrious moon explorers were naturally impatient to be reunited with their families and to relax after their long, incredible travels. But for Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins such ordinary pleasures will have to be postponed for quite a few weeks to come. The rest of the world may have gone back to a normal earthly routine, but for the three men who recently blazed the lunar trail, Apollo's mission is still far from over.

After the astronauts were scooped up in their recovery capsule by naval helicopter, they were taken aboard the USS Hornet to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory near Houston. The lab is a massive complex of medical and scientific buildings which serves as the reception quarters for returning space travellers. Here the astronauts will remain in quarantine for 21 days and undergo a series of rigorous tests to determine if they have suffered any biological side effects from their lunar odyssey. They are presently sealed off in pre- sterilized dormitories and they have been wearing biological isolation suits since the moment of their splashdown. Until scientists can determine for certain whether the astronauts have been exposed to some dangerous moon virus, precautions must be maintained. Even the Apollomen's wives and children have not been allowed to enjoy a real visit with the conquering heroes. Such traditional informalities as family hugs and kisses have to wait until the astronauts have received a complete medical o.k. For the time being, brief conversations, with the astronauts separated from visitors by an enclosed glass booth, will have to suffice. Such is the price our astronauts must pay for their glory.

The only persons whom the astronauts have come into actual contact with since their return are the specially selected staff at the receiving lab. This staff consists of fifteen trained space experts who will minister to all the astronauts' needs during their period of detainment. There are doctors on hand to carry out the medical part of the program as well as a cook and housekeeper to perform domestic chores. Otherwise, the astronauts are completely sealed off from the outside world.

The dormitories which the heroes are occupying during their stay at Houston are sparsely furnished but comfortable. Each room contains only a single bed, night table and reading lamp. By an intricate system of electronic vacuuming pipes and filters, the rooms are kept in a continual state of sterilization.

Right now technicians at Houston are performing hundreds of tests and experiments to learn if the astronauts have indeed contracted some unknown moon disease. Most likely these tests will prove negative. But because of the enormous risk involved, the quarantine stage is as important a part of the program as the lunar landing itself. Scientists know that if our moon voyagers were susceptible to some invisible lunar microbe, human antibodies might prove powerless to combat the germ. Therefore, every precaution is being taken now to insure the future health of the astronauts and the world at large. •

Click to join 3rdReichStudies

Armstrong: There seems to be no difficulty in moving around, as we suspected. It's even perhaps easier than the simulations of one-sixth G (one-sixth earth gravity) that we performed in various simulations on the ground. No trouble to walk around. Okay, the descent engine did not leave a crater of any size. It's, uh, there's about one-foot clearance from the ground. We're essentially on a very level place here. I can see some evidence of rays emanating from the descent engine, but very insignificant amount. Okay, Buzz, we ready to bring down the other camera?

Armstrong: There seems to be no difficulty in moving around, as we suspected. It's even perhaps easier than the simulations of one-sixth G (one-sixth earth gravity) that we performed in various simulations on the ground. No trouble to walk around. Okay, the descent engine did not leave a crater of any size. It's, uh, there's about one-foot clearance from the ground. We're essentially on a very level place here. I can see some evidence of rays emanating from the descent engine, but very insignificant amount. Okay, Buzz, we ready to bring down the other camera?